21 Markets Overvalued Based on Fundamental Factors of Price-to-Income and Price-to-Rent

Talking about housing bubbles usually raises questions, concerns and eyebrows. However, for the past several years, home prices have continued to rise throughout the country, with many markets close to or above previous peak levels observed in the 2005-2006 bubble years. At the national level, Figure 1 shows that home prices have increased roughly 40 percent, according to the CoreLogic Home Price Index (HPI), over the four-year period since January 2012. Given such a strong growth rate, one natural question is “are we heading toward another housing bubble like 2005 – 2006?”

In order to answer this question, first we need to define what a bubble is. According to Joseph Stiglitz (1990)[1], the Nobel Laureate in Economics,

“[I]f the reason that price is high today is only because investors believe that the selling price is high tomorrow – when ‘fundamental’ factors do not seem to justify such a price – then a bubble exists.”

Based on this definition, the high price growth rate alone of more than 40 percent over four years, in itself, is not evidence of a housing bubble. In order to determine the existence of a bubble, we need to first identify fundamental factors in housing markets and see whether the high house price growth rates can be justified by these factors. Secondly, we need to identify metrics to capture the belief that “selling price is high tomorrow.” In Part I of this blog series we will examine two metrics for measuring the fundamental factors: price-to-income and price-to-rent. In Part II we will expand the analysis to two extra metrics for measuring speculative activities. Lastly, applying these four metrics to the top 100 Core Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs), in Part III we will discuss how to manage potential risks with precision and discipline in these overvalued markets.

For fundamental drivers of housing markets, one camp in housing economics is the price-to-income view, in which, in the long run, there is a stable relationship between house price and income. For example, Case and Shiller (2003)[2] show that “income alone almost completely explains home price increases in the vast majority of states.” In most states, the price-to-income ratio is very stable. CoreLogic published the Market Condition Indicators in April 2014 in which the long-run sustainable HPI level is derived from the historical co-integration relationship between home price index and disposal income per capita. The Market Condition Indicator is based on the principle that home prices cannot outpace growth in household income forever. Because disposal income usually represents peoples’ ability to pay, intuitively there should be an established long-term relationship between income level and home prices. Over the shorter periods, home prices can exceed or fall below the long-run trend, but over a longer time, home price growth cannot be sustained above income growth indefinitely because housing would become unaffordable. Demand would decrease causing home price growth to either slow down or decline, thereby realigning with income levels. In each market, CoreLogic calculates the gap between actual HPIs and their long-run sustainable levels. Using 10 percent as the threshold, we define an “overvalued market” as one in which the home price is more than 10 percent of its long-run sustainable level.

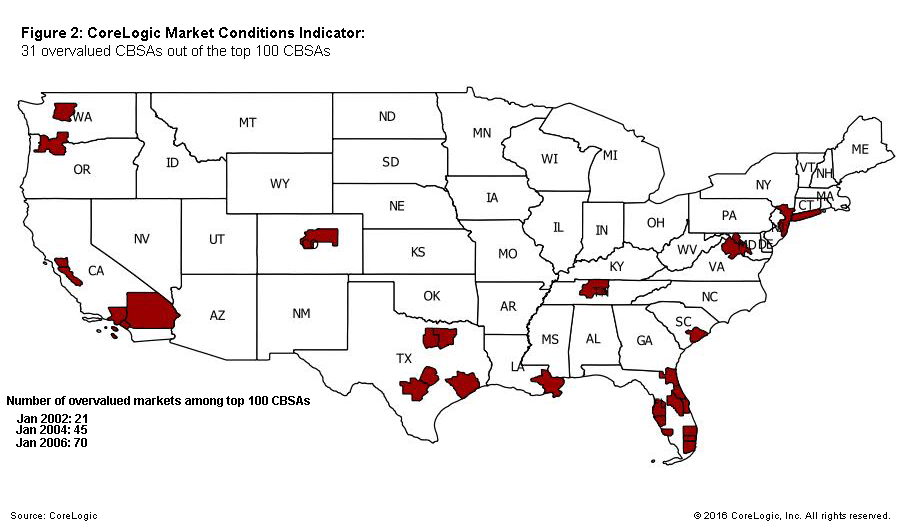

Figure 2 displays the overvalued markets as of April 2016. There are 31 overvalued markets among the top 100 CBSAs. On the west coast, Seattle, Portland and a few California markets are overvalued. On the east coast, overvalued markets include New York, DC and a number of Florida markets. In the midwest, it is mainly Texas markets. To put the numbers into perspective, when we apply the same metric to historical data, we find, among the top 100 CBSAs, 21 overvalued markets in January 2002, 45 for January 2004 and 70 for January 2006. If (a big if) we were heading toward another bubble like in years 2005 and 2006, we are at a stage equivalent to year 2003.

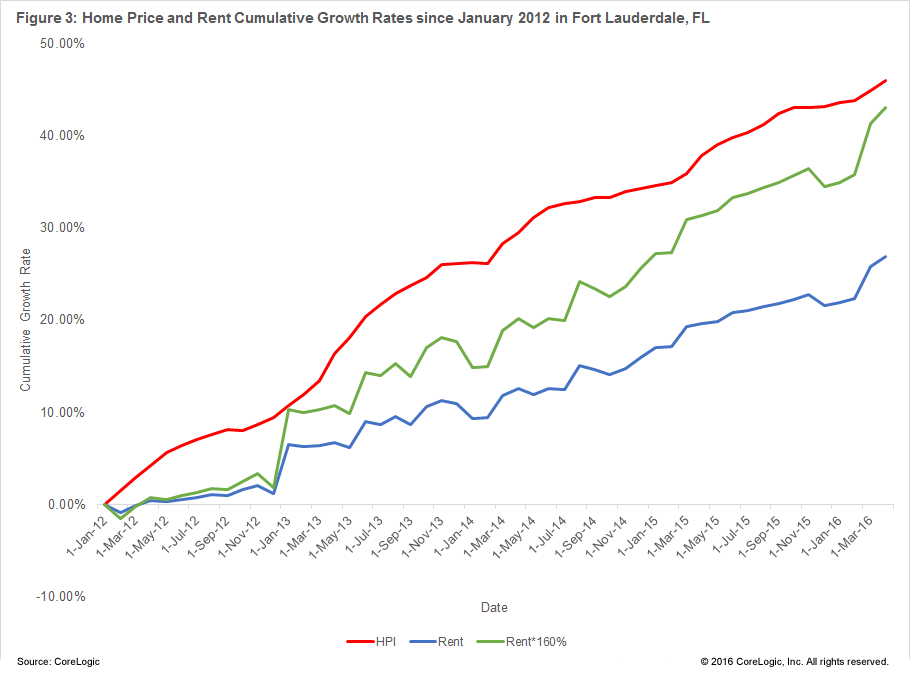

Besides the price-to-income view, another popular camp in housing economics is the price-to-rent view. Renting is an obvious alternative to home ownership, yielding a similar flow of housing services to a family. Rent is the price to pay for that flow, or an opportunity cost of living in one’s home rather than owning it. Over the long run, market forces should equalize the cost and benefits of home ownership and renting, if sufficiently liquid rental and housing markets exist. CoreLogic has a RentalTrends[3] database, in which, among other things, we track average and median rent payments for single-family rentals at various geographical levels. Since single-family rental units became widespread only after institutional investors started buying and renting them out during the Great Recession, our RentalTrends database started tracking this metric in January 2012. Given the short history of rental data, it is difficult to build a statistical model between home price and rent similar to the analysis of home price and disposal income in the Market Condition Indicator. Fortunately, there are studies[4] showing that the price-to-rent ratio during the bubble years was at most 60 percent higher than the long-run average price-to-rent ratio, implying that home prices can grow 60 percent faster than rent[5]. Here, I use 60 percent to construct a rule of thumb metric on the price-to-rent ratio to assess whether a market is overvalued.

Figure 3 displays the cumulative growth rates of home price and rent payment since January 2012 for Fort Lauderdale, FL. I inflate the rent growth rate by 60 percent to construct the threshold for market overvaluation from the rent perspective. The light green in the graph is the rent growth rate, multiplied by 160 percent, the maximal deviation of the price-to-rent ratio we observed during the bubble years. If the home price growth rate in a specific CBSA is above the light green line, the inflated rent growth rate, then this CBSA is declared as overvalued. In Fort Lauderdale, FL, the cumulative home price growth rate is about 46 percent, above the threshold of 43 percent (actual rent growth rate of 27 percent since 2012 x 160%). Hence, it is classified as overvalued.

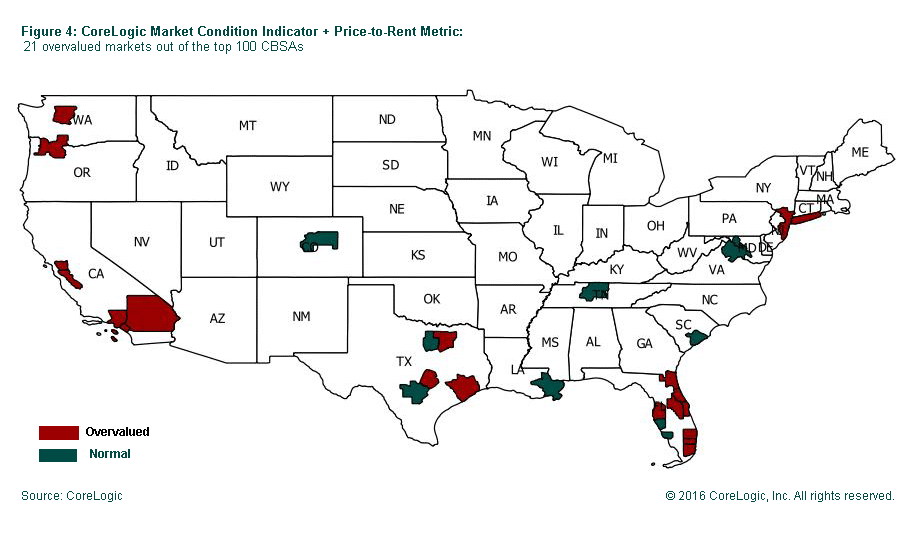

Applying this price-to-rent metric to the 31 markets identified by the CoreLogic Market Condition Indicator in Figure 2, we find 10 of them are not overvalued from the price-to-rent perspective. Figure 4 illustrates that many midwest markets are removed from the overvaluation list. Table 1 lays out the details for the remaining 21 overvalued markets. In Part II of this blog series, we will further examine speculative activities in these markets.

- Stiglitz, J. E. (1990), “Symposium on Bubbles,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 4(2), Spring, pp. 13-18

- Case, K. and R. Shiller (2003), “Is There a Bubble in the Housing Market? An Analysis,” prepared for Brookings Panel on Economic Activity.

- https://stage.corelogic.com/downloadable-docs/capital-markets-rentaltrends.pdf

- For example, Himmelberg, C., C. Mayer, and T. Sinai (2005), “Assessing High House Prices: Bubbles, Fundamentals, and Misperception,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 19, no. 4. Glick, R., K. Lansing and D. Molitor (2015), “What’s Different about the Latest Boom?” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter.

- There are numerous studies in academics and industry regarding the “cap rate compression” in commercial real estate markets, where cap rates fell significantly over time. (See, for example, Chervachidze and Wheaton (2011), “What Determined the Great Cap Rate Compression of 2000-2007, and the Dramatic Reversal During the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis?” Journal of Real Estate Financial Economics.) The appropriate level of cap rates was widely discussed and debated amongst the “new paradigm” and “housing price bubble” camps. Cap rates are inversely related to price-to-rent ratio. If the compressed level of cap rate is the new normal, then price-to-rent ratio can stay elevated relative to its historical long-run average. However, while cap rate compression is widely cited in commercial real estate markets, few studies have been done on single family markets. Furthermore, since my analysis period is only 4 years, cap rate movements in single family markets should have little impact.

© 2021 CoreLogic, Inc. All rights reserved.