U.S. median single-family home property taxes have risen by more than 25% since 2019

For U.S. homeowners, annual property taxes are a direct, out-of-pocket cost that impacts budgets. As U.S. home prices have continued to rise and reach record highs, millions of owners are feeling the pinch from soaring property taxes.

In particular, the 2023 property-tax assessment cycle followed major home price gains during the pandemic. The U.S. housing market recorded a nearly 40% price increase between 2019 and 2022, making it one of the hottest in history. [1] Property taxes are based on a home’s assessed value and can vary from state to state or by county or municipality. But almost invariably, property taxes typically increase over time as values rise.

Local tax assessors periodically reassess properties based on an assessment cycle. Assessment cycles are governed by state laws and standards but are commonly determined locally depending on statutory provisions. Consequently, the shorter assessment cycles that local tax officials adopt, the more closely assessed values will reflect property’s prevailing market value, and the more frequently property taxes will increase. In practice, assessment cycles can be as short as one year or as long as 10 years. [2]

As the 2023 assessment cycle ends, homeowners who live in states or tax jurisdictions where properties are subject to annual reassessments (or have been recently reassessed) have likely seen property taxes balloon, particularly in areas where home prices rose substantially during the pandemic.

How Much Have Americans’ Property Taxes Changed Since the Pandemic?

Figure 1 shows median property taxes in 2023 and 2019, displayed separately depending on whether properties were reassessed during the tax years. In 2023, U.S. median property taxes for all properties (whether there was a reassessment or not) reached $2,826, up by $539 from 2019 and representing an increase of 23.6% over that period, averaging 5.9% per year.

Among reassessed properties, median property taxes in 2023 were $2,943, up by $612 or 26.3% since 2019, averaging a 6.6% increase per year. In comparison, median property taxes were $315 lower at $2,592 for homeowners whose properties were not reassessed. Also, non-reassessed properties showed a smaller increase between 2019 and 2023, up $402 or 18.4%, averaging 5% per year.

A Look at Annual Property Tax Rates and Costs by State

At the state level (Figure 2), property taxes differ widely. The states with the lowest median property taxes in 2023 were West Virginia ($694), Alabama ($708), Arkansas ($847) and Mississippi ($896). Median property taxes were the highest in New Jersey ($8,498), Connecticut ($6,103) and New York ($6,043). The states with the next-highest property taxes include California, Texas, Vermont, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Massachusetts, where median annual payments fall between $4,500 and $6,000.

Varying property taxes are primarily due to differences between home values and property tax rates. Also, differences in state laws that limit annual increases in assessment values are important factors, as they affect how fast property taxes can go up annually, regardless of the market rate of home price appreciation.

For instance, California caps reassessment increases at 2%, while Texas homeowners are subject to a 10% cap per year. The less-restrictive cap in Texas on assessments means that many homeowners there have likely seen their property taxes move up much faster than their counterparts in California – despite the fact that both states have seen some of the largest home price appreciation over the last few years.

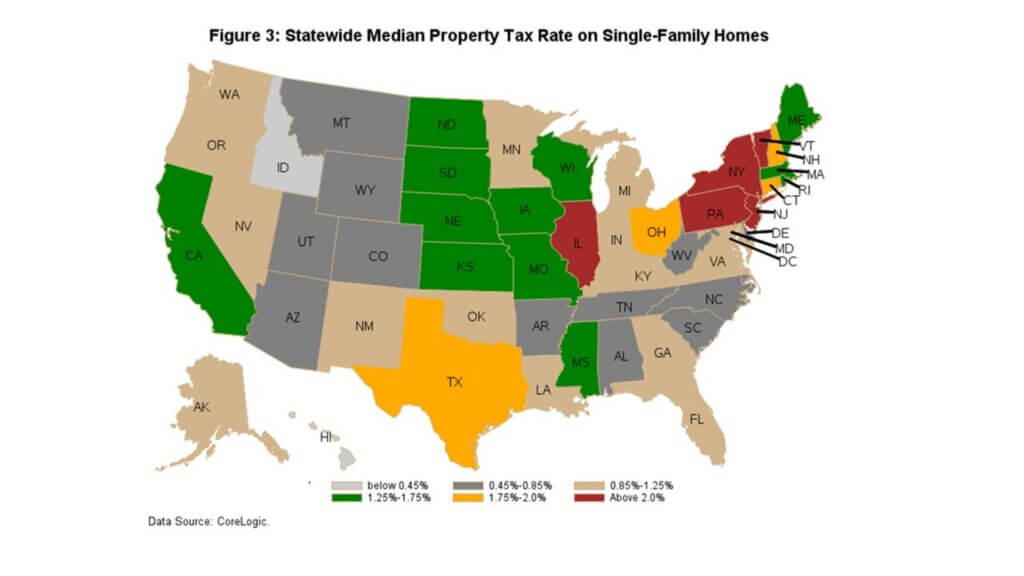

For median property tax rates at the state level, see Figure 3, where the median value is based on the effective tax rate calculated for individual properties and on the amount billed to the homeowners after homestead exemptions and credits are factored in. Property tax rates range from as low as 0.3% in Hawaii to as high as over 2% or more in states that include Illinois, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey and Vermont. Idaho has the second-lowest rate following a massive legislative tax cut in 2023, benefiting homeowners with an 18% reduction in property taxes on average. In 2023, annual median property taxes in Idaho were $1,718.

It is important to keep in mind that these numbers above represent state averages. Local U.S. jurisdictions, counties and municipalities determine and govern property taxes, so where exactly you buy a home will determine your actual rate and yearly costs.

CoreLogic’s Office of the Chief Economist’s home page has the latest commentary from our team of housing industry experts, including our monthly market reports, so be sure to check back on a regular basis for more.

[1] Source: CoreLogic Home Price Index

[2] Source: National Association of Counties

©2024 CoreLogic, Inc. All rights reserved. The CoreLogic content and information in this blog post may not be reproduced or used in any form without express accreditation to CoreLogic as the source of the content. While all of the content and information in this blog post is believed to be accurate, the content and information is provided “as is” with no guarantee, representation, or warranty, express or implied, of any kind including but not limited to as to the merchantability, non-infringement of intellectual property rights, completeness, accuracy, applicability, or fitness, in connection with the content or information or the products referenced and assumes no responsibility or liability whatsoever for the content or information or the products referenced or any reliance thereon. CoreLogic® and the CoreLogic logo are the trademarks of CoreLogic, Inc. or its affiliates or subsidiaries. Other trade names or trademarks referenced are the property of their respective owners.