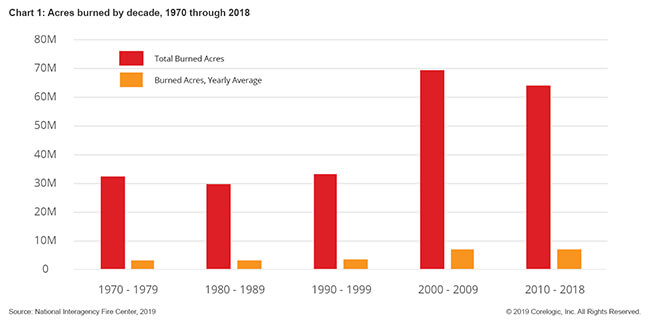

Over the past several years, the United States has experienced record-breaking wildfires. In 2018 alone, a total of 8,767,492 acres burned – an area roughly equivalent to 74 of the 75 largest cities in the United States combined. This is the sixth-highest total since modern historical records began in the mid-1900s.

In 2004, over 8 million acres burned in one year – this happened another eight times in the following 14 years. A decadal comparison of burned acreage shows that there has been a shift towards increased burned acreage over the last 20 years. Within this same timeframe, larger and more devastating wildfire events have occurred, particularly in areas with increased wildfire risk.

CoreLogic compiled a list of the top 15 metropolitan areas with homes at elevated risk to better understand the landscape of risk outside of what is typically considered a wildfire hot spots, e.g. large swaths of unoccupied forest. All 15 are within the Western U.S. based on combined high- and extreme-risk properties along with the Reconstruction Cost Value (RCV) for each. The rank is based on the RCV.

Risk in metro areas is interesting, as wildfires in the Western U.S. have always been a part of the ecosystems and landscapes. For example, in areas without human habitation, lightning strikes were often the source of natural ignitions. However, the population of this area of the country now tops 100 million and thus the potential impacts of wildfires on humans, and vice versa, are inextricably linked. People are more likely to cause wildfire ignitions by a factor of 4-to-1 compared to natural causes. While some human-caused ignitions are the result of arson, many are caused by accidental or unintentional ignitions from normal human activity such as lit cigarettes and campfires.

As demand for housing grows and development expands outward from large cities, the wildland urban-interface, a transition zone between unoccupied land and human development, is often the only location with space to expand. Very frequently, that edge of development will border wildfire-prone vegetation.

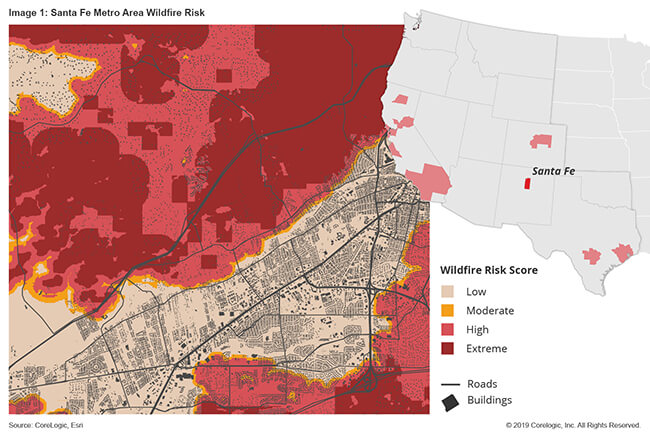

To illustrate wildfire risk in the United States, the snapshot below highlights Santa Fe, New Mexico – ranked 12 out of the top 15 metro areas with elevated risk.

In analyzing the Santa Fe metro area, it’s easy to see how low risk doesn’t necessarily mean no risk. The border between low-risk and extreme-risk areas is slender, and major highways snake in and out of extreme-risk areas, which means that if a fire broke out, the community may have a more difficult time evacuating, Additionally, the bottom-right side of the image shows the Santa Fe Regional Airport lays against three different risk areas: moderate, high and extreme. In more extreme circumstances, embers from fires in extreme risk areas can be blown a mile or farther and ignite structures. Many homes are destroyed each year due to ember-related ignitions.

Last year, the Camp Fire devastated the city of Paradise, California. The fast-moving fire and limited road network in and out of Paradise prevented residents from leaving quickly, leading to the largest loss of life due to a wildfire in California’s history. In addition, the Camp Fire destroyed 18,804 structures – more than the 10 most destructive California wildfires combined. CoreLogic estimates the total losses from the Camp Fire at $9.3 billion.

When considering the future of wildfire risk in the Western U.S., it will likely expand to more homes and result in greater property losses than we have seen in the past.

Wildfire is a unique peril because the level of damage is often binary – meaning, a home is either left untouched by the fire, or a total loss occurs. A patchwork of devastation occurs as fires pass by some properties indiscriminately while surrounding homes are reduced to ash. Unlike flooding or hail, wildfires can and often do result in a 100% loss of the structure. Post-event studies have shown that structural hardening, or the process of mitigating a home against wildfire (e.g., using fire-resistant building materials for roofs, siding, etc.) can increase a home’s resistance to fire. However, all too often luck seems to play a part, too.

It only requires less than perfect weather conditions and an errant spark to create the next unwanted record for wildfire damage or loss of life.

For an in-depth look back at major wildfire events in 2017 and 2019, or for more information about regional, state or national wildfire risk in the United States, read the CoreLogic 2019 Wildfire Risk Report.

© 2019 CoreLogic, Inc. All rights reserved